2021 Minnesota Principals Survey (MnPS)

The Minnesota Principals Survey (MnPS) aims to elevate principal voice. Findings and reports stemming from the initial administration of the MnPS in 2021 (published between 2021 and 2023) are hosted here. For more recent findings and publications stemming from the second administration of the MnPS in 2023 (published since April 2024), refer to the main MnPS page.

Access 2021 MnPS Data in Tableau

Thanks to funding from The Minneapolis Foundation and The Joyce Foundation, the data from the 2021 MnPS is now available in Tableau, a data visualization platform that allows anyone to access the de-identified data. The data can be accessed by the type of question as explained on the Table of Contents tab. From there it can be disaggregated by numerous variables including participant race/ethnicity, gender, school level, and others. We hope that you find this data useful.

Main Report (2021)

This report covers the methodology and findings of the initial administration of the MnPS in November 2021. It was originally published in 2022.

Executive Summary (2021)

The executive summary covers key findings and takeaways stemming from the initial administration of the MnPS in 2021. It is not intended to replace the full report and was originally published in 2022.

1-Page Summary

This one-page summary provides an at-a-glance overview of some findings from the initial administration of the MnPS in 2021. It was published in 2022.

Policy and practice briefs

Policy and practice briefs: Overarching recommendations

Synthesizing 779 responses to a 70-question, comprehensive survey about the principalship along with the feedback of 49 leaders in 9 focus groups into a brief set of recommendations is not simple; however, a lengthy list would not be useful, either. Therefore, our overarching recommendations each address four critical needs communicated through the survey and focus groups by principals: Time, Training, Trust, and Transformation—the four T’s.

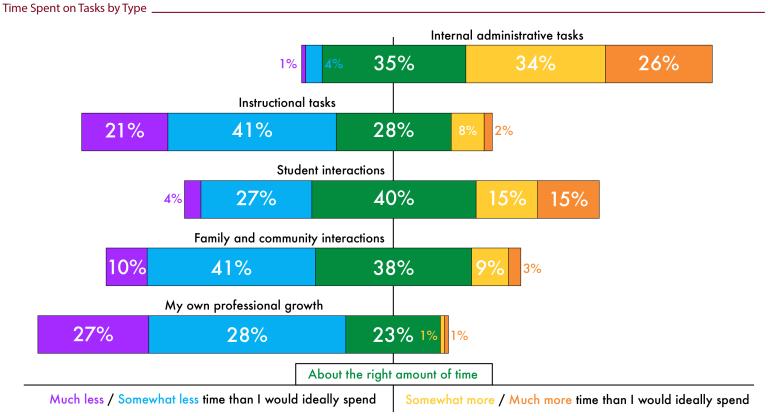

Time. Over and over again, principals conveyed time as an issue. In the survey, they told us they spent more time than they would like on administrative tasks and less time than they would like on instructional leadership and family and community engagement. They told us there is not enough time for their own professional growth or engagement in policy influence. In focus groups, they reiterated that daily ‘urgent’ tasks (e.g., finding substitute teachers, responding to mental health crises) take time away from more strategic tasks like teacher coaching and curricular alignment.

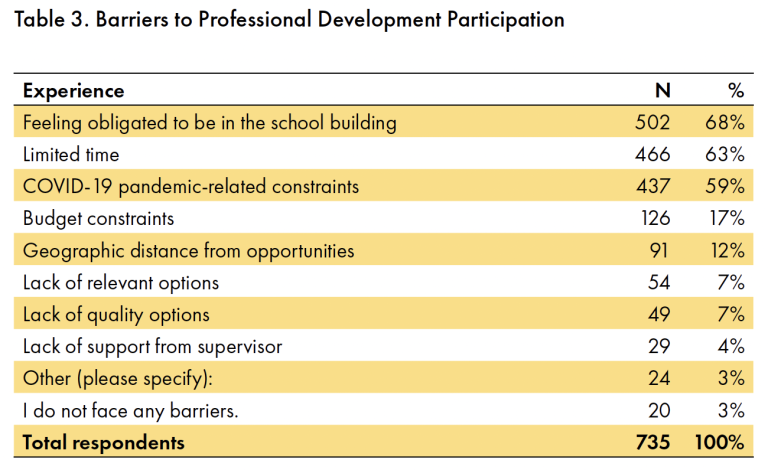

Training. Overwhelmingly, principals told us they needed more and better training. On one hand, leaders felt their licensure programs had prepared them well to carry out the management and decisionmaking aspects of their jobs. On the other hand, respondents lacked confidence in instructional leadership—the aspect of their job that nearly 80% said was their primary role— specifically as it relates to culturally responsive instructional practices. They cite feeling obligated to be in their buildings, limited time, and a lack of access to high quality, research based professional development as obstacles to their own growth and improvement as leaders.

Trust. Principals report high levels of job satisfaction and that they feel their work is valued by the staff at their school; however, they also expressed trepidation about leading amidst community division and facilitating conversations about gender identity and race. Principals wanted their supervisors to trust and support them—to ‘have their backs’ when needing to make an unpopular decision or lead an uncomfortable conversation.

Transformation. The role of the principal is immense, and more than half of principals tell us that their workloads are not sustainable. While 90% of leaders tell us they feel that they can be successful leading their schools, to support their sustainability may require transforming key aspects of the principalship. Investments in high-quality, sustained professional development, fundamental restructuring of the use of time and resources, and sustained support will all need to take place. Our recommendations center the transformations that could take place in order to ensure the role of school leader is truly transformational.

Recommendation 1: developmental approach to initial training, internship, and ongoing professional development

Both the MN Principal Survey data and the follow-up focus groups highlight a need for a developmental approach to principals’ initial training and internship experiences and to their ongoing professional development. The vast majority of those entering the principalship have certification and experience in education. However, those experiences and their credentials are varied, giving some more experience in literacy and others more experience in mental health. We argue that candidates’ prior credentialing and experiences should be accounted for in the crafting of their initial training programs, thus allowing for an approach that meets their content and developmental needs. This approach can and should be carried through into the internship experience, which we feel should be significantly broadened as well as into the ongoing professional development experiences of licensed administrators.

Initial Training. Our survey data demonstrates that leaders feel their initial preparation programs solidly prepared them in areas that largely fall into the category of management and decision making while they report feeling less prepared in areas like instructional and culturally responsive school leadership. Licensed Minnesota principals are highly credentialed with a minimum of 60 credits beyond their bachelor’s degree and a demonstration of entry level competency in 86 competencies per Minnesota Administrative Rule 3512.0510. However, 58% of principals reported ‘culturally responsive teaching’ was missing from their administrative licensure coursework. While some licensure programs have made great strides toward including coursework in culturally responsive teaching, we recommend that all licensure programs do so. We recommend that initial licensure should include courses that directly address instructional leadership, especially conceptual frameworks from key content areas like literacy, mathematics, science, and history, in which principals may have had little to no training in pursuing their initial teaching license. Given there are few required courses in curriculum and instruction or instructional leadership in traditional “leadership” MEd programs, including them as part of administrative licensure is crucial. Additionally, candidates should be allowed and encouraged to take content courses that will benefit their own personal development. For example, an elementary teacher steeped in literacy seeking the K-12 principal license should likely not be required to take more coursework in literacy, but rather focus on content specific curriculum they do not have sufficient experience in, like science or special education. Administrative licensure programs could help advise and ensure students are getting content specific courses as they pertain to instructional leadership based on what the candidate’s initial licensure was, what coursework they had in their initial master’s degree and what specific and significant professional development they have engaged in during their career.

Internship. Currently those seeking principal licensure must complete a 320 hour internship with 240 of those hours being completed at the elementary, middle, or high school level and the remaining 80 hours between the other levels. These hours are traditionally completed while the candidate holds a full-time job. This means the candidate and their mentor are left trying to craft experiences that are not truly part of the candidate’s day-to-day experience. We recommend that the administrative internship should be a paid internship where the candidate is immersed in the day-to-day work in a full-time manner. Given the overwhelming feedback from practicing principals is that they do not have enough time for instructional leadership and also considering that the “urgent” is often prioritized over the important, the position of administrative intern would not only provide a genuine and deep learning opportunity for the licensure candidate, but also benefit the school and district as a support to the principal. In addition to the added support the intern could provide, this could also serve as a ‘grow your own’ leadership program for the district. The RAND Corporation has found that Principal Pipelines are “feasible, affordable and effective” (Gates, Baird, Master, & Chavez-Herrerias, 2019). This more extensive internship would allow future principals a few added advantages over the current internship model often used:

- Interns would be able to be placed with effective, experienced leaders they could learn from, not necessarily the principal of the school in which they currently work.

- Interns would be engaged in the day to day operations of a school for an entire school year, allowing them to experience important administrative tasks that are cyclical, like staffing and scheduling, professional development and evaluation of staff, community engagement, budgeting, curriculum development, initiative implementation and monitoring, and the school improvement process.

- A year-long internship would allow for candidates to also work with their mentoring principal to identify their strengths and opportunities for improvement as a leader so that as they transition into their first administrative role, they could have a clear understanding of the professional development, support, and opportunities they will need as they grow.

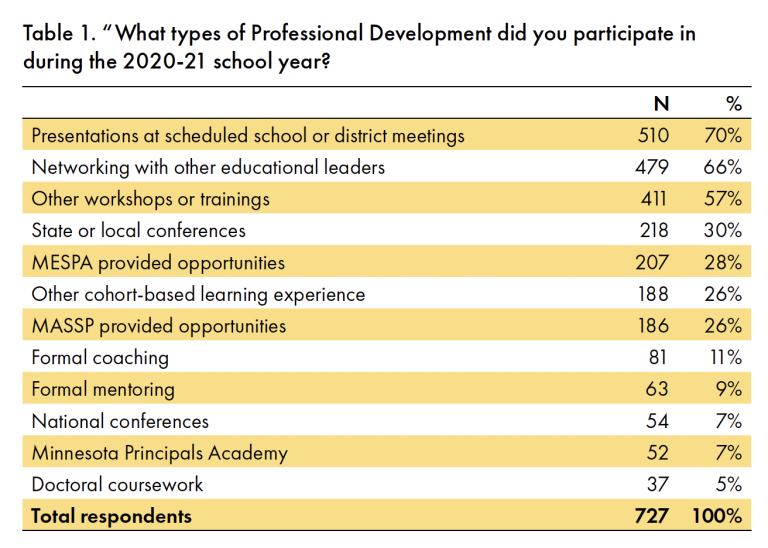

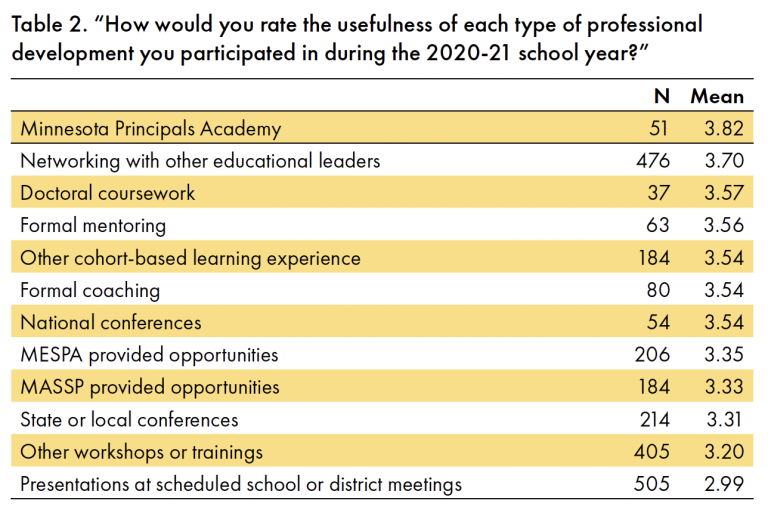

Ongoing Professional Development. The ongoing professional development of a licensed principal—in theory—should be guided by the annual principal development and evaluation plan outlined in Minnesota Statutes 123B.147 subd. 3. Among other requirements,1 the principal’s evaluation must “be consistent with a principal’s job description, a district’s long-term plans and goals, and the principal’s own professional multiyear growth plans and goals” (emphasis ours). In alignment to this requirement, the Minnesota Department of Education has developed resources to support a growth-focus evaluation and professional development through their Principal Leadership Support work. However, over a third (35%) of respondents to the MnPS did not feel that their performance evaluations helped them grow in their leadership practice (Pekel et al., 2022). We suspect this may reflect a lack of alignment between principals’ evaluations and the kinds of professional development they regularly have access to. In fact, principals also told us that the type of professional development they most often engage in, presentations as scheduled school or district meetings, is the kind of PD they deemed least useful. Focus group participants described more useful PD opportunities as those that allowed them to discuss the specific challenges they faced—such as networking opportunities with other educational leaders—in the context of a “culture of adult learning.” We recommend that the ongoing professional development that principals engage in should be based on their developmental needs as determined in collaboration with their supervisor as a result of the formal evaluation process. Much like our recommendation in initial licensure, we believe that leaders should be engaging in professional development for growth, versus a one-size fits all approach.

1. Statutory requirements for principal evaluation in Minnesota now include new language following the 2023 legislative session: “The evaluation must:... (2) support and improve a principal’s culturally responsive leadership practices that create inclusive and respectful teaching and learning environments for all students, families, and employees” (Laws of Minnesota, 2023,). Such a requirement lends itself to more personalized, developmental approaches to principal learning and improvement, not one-size-fits-all training experiences.

While the “how” of principal professional development, the approach described above is important, this recommendation addresses the “what.” Survey and focus group data not only highlighted that common, one-size-fits-all trainings were ineffective, but they also highlighted concerningly low self-efficacy in several core dimensions of the principalship, namely instructional leadership, culturally responsive school leadership, and creating psychologically safe and humanizing school environments. We recommend that the Board of School Administrators should, in consultation with practicing principals, adopt specific content area requirements for continuing education units (CEUs) in areas such as these. While there are currently no specific requirements for administrator re-licensure in Minnesota beyond the required 125 Clock Hours, there are for teachers: according to Minnesota Administrative Rule 8710.7200, to renew a Tier 3 or Tier 4 teaching license, with limited exceptions, educators must engage in professional development in five specific areas:

- Positive behavior intervention strategies

- Reading preparation

- Key warning signs of early-onset mental illness in children and adolescents

- English learners

- Cultural competency

Other states, like Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, require principals to pursue continuing education in specific content areas, much as Minnesota does for teachers. While selection of specific trainings should be left to individual leaders and perhaps their supervisors, we recommend that school leaders be required to earn CEUs for professional development in three broad areas:

Instructional leadership. Survey respondents told us that instructional leadership is the broad domain of leadership in which they feel the least confident, compared to the domains of management and decision making, school improvement, and climate and culture. This is especially problematic given that nearly 80% of survey respondents viewed their primary role as being an instructional leader. Furthermore, many principals shared that their administrative licensure programs did not include coursework in culturally responsive teaching—a critical component of instructional leadership.

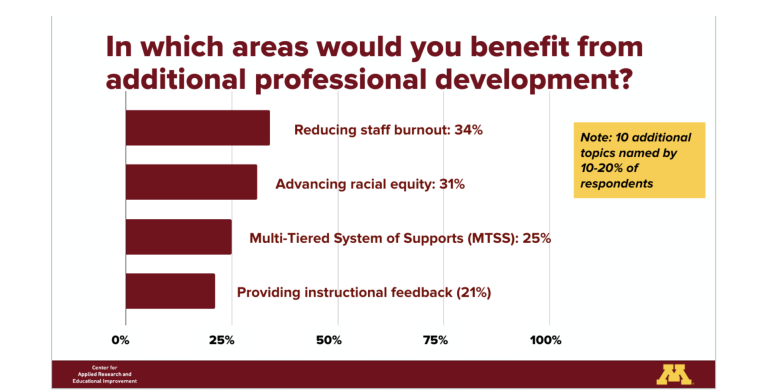

Culturally responsive school leadership. Out of 30 leadership domains, survey respondents felt least prepared in supporting instruction that is culturally responsive and leveraging students’ cultural backgrounds as assets for teaching and learning. Additionally, 46% of respondents told us a key experience missing from their internship experience was facilitating conversations about equity. When asked to select the areas in which they would most benefit from additional professional development, principals selected advancing racial equity more than every other topic besides reducing staff burnout.

Creating psychologically safe and humanizing school environments. To create safe and humanizing school environments, leaders must be able to do many things, like facilitate dialogue that supports LGBTQ+ students, ensure racial justice, reduce bullying, address staff burnout, and engage families and communities in decision making, to name just a few. The importance of this work is underscored by the most recent Minnesota Student Survey results, which show that LGBTQ+ youth report being bullied and indicate having had suicidal thoughts at much higher rates than their non-LGBTQ+ peers. It’s clear students and staff need our leaders to have the confidence and skills to create psychologically safe and humanizing school environments, and yet MnPS survey and focus group data suggest that leaders are struggling to do so. In light of the serious—and potentially tragic—consequences of failing to act in response to these challenges, we believe that principals should be required to engage in professional learning in this area as they seek CEUs for relicensure.

How the four T’s are addressed in this recommendation

Time. Professional development takes time, and often requires leaders to be out of their buildings. However, a more strategic approach to development—one that takes leaders’ strengths and areas for growth into consideration, rather than a one-sizefits- all approach—will ensure principals’ PD time is useful to them. Principals who engage in PD experiences that address their areas for growth, specifically, will be well-positioned to improve their leadership practice, leading to better opportunities and outcomes for students. Furthermore, the approaches to professional development leaders cited as the most useful were ones that happened over a longer period of time with a cohort of trusted peers, like doctoral coursework and the Minnesota Principals Academy.

Training. When we asked leaders on the MnPS what they most needed to address their greatest challenges, increasing my knowledge or skills and tools or frameworks were consistently the top two selections, across nearly all areas of leadership (Pekel et al., 2022). Training is clearly needed; however, this training should be developmental and personalized in nature, not “sit-and-get.” Opportunities for conversation, networking, and learning from one another can bolster the effectiveness of training. Additionally, our survey and focus group data tell us that BIPOC leaders may have different needs than White leaders, again pointing to the need for a more personalized approach.

Trust. Research literature suggests that small groups of leaders engaged in professional learning on an ongoing basis, over time, leads to more trusting spaces where deep learning can take place (Darling-Hammond, Wechsler, Levin, Leung-Gagné, & Tozer, 2022). We also know that a trusting relationship between a principal and their supervisor is paramount to effective professional development. In a recent study, Dr. Peter Olson- Skog (2022) found that Minnesota principals defined a trusting relationship as including the following:

- Time investment—Principals want their supervisors to engage with them regularly, informally, and at their schools, where supervisors could “see them in action” and understand the current realities of their day-to-day work.

- Setting clear expectations—In addition to clearly communicating expectations, principals want supervisors to create a safe space for a dialogue in which principals help shape and clarify the expectations without appearing insubordinate. Principals desire particular clarity around their level of authority in decision-making.

- Collaboration—Principals cite a strong desire to work side-by-side with their supervisors as colleagues, not subordinates, where appropriate. Principals want to cocreate school-related policies, curricula, and improvement plans with their supervisors. They want to co-reflect on new learnings and the success (or lack thereof) of current initiatives with their supervisors. Finally, they want to colead (e.g., a district professional development session).

- Personal knowledge—Principals want their supervisors to know them personally and professionally. They do not need to be friends, but they want their supervisors to know them as a person, not just as an employee.

Further, principals recommend dispositions (or character traits) that strengthen the needed trusting relationship. Principals desire supervisors who are caring, vulnerable, and predictable. When supervisors demonstrate care for principals, knowing them personally and professionally, principals are more apt to trust that their supervisor’s expectations are reasonable. When principal supervisors are vulnerable, showing their humanity and acknowledging their mistakes, principals are more likely to do the same. This creates the trust and room for risk-taking needed for authentic collaboration and co-creation. Finally, principals want their supervisors to be predictable and consistent. A lack of predictability and consistency leaves principals guessing how they need to navigate the relationship with their supervisor on a given day. This drains trust, especially when principals guess wrong.

Transformation. A transformation is needed in the way we typically approach principal professional development in Minnesota. Growth and development opportunities should be personalized to meet school leaders’ specific needs, and provide ongoing peer/supervisor reinforcement and support. It’s time to abandon “sit and get” and “one and done” PD, which principals do not find useful. If new learning is introduced, that learning needs to be revisited, coached, and applied in practice. A developmental approach to ongoing learning could also transform many principals’ feelings of isolation in their day to day work through a community of practice.

Recommendation 2: A different school leadership model

Few would dispute that the principalship can be a very challenging job. In our survey, 54% of respondents reported that to some degree, their current workload is not sustainable. In order to ensure that we can continue to recruit and retain school leaders, we argue for a different model for school leadership. The principal matters. This is evident across numerous research studies, and likely anyone reading this report would agree (Grissom, Egalite, & Lindsey, 2021; Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2001; Wahlstrom, Seashore Louis, Leithwood, & Anderson, 2010). Because 54% of leaders tell us their workload is not sustainable, that overall they lack the time and confidence to be an instructional leader, and that engagement with and inclusion of families—specifically marginalized families—is something that is not happening on a regular or widespread basis, we propose a different model for school leadership that distributes these essential leadership functions. In their seminal study examining how school leadership impacts student learning, Louis et al. (2010) called for the “substantial redesign” of the principalship (p. 103), including the distribution of leadership between teachers, parents, and district staff. In reference to leaders’ persistent lack of capacity to enact instructional leadership, the study authors conclude that:

In order for principals to devote more time and attention to the improvement of instruction, their jobs will need to be substantially redesigned. In many schools this will require the creation of other support roles with responsibility for managing the important tasks only indirectly related to instruction… Differentiated administrative staffing—with different administrators assigned to managerial and academic roles—is one example of changes that merit exploration. (p. 103)

As urgent “fires” upend principals’ best laid plans, they are not getting to do the things they believe are important, like instructional leadership, engagement with families and community, and their own professional development. The reality is that the job(s) of a principal are far too many for one person.

In response to decades of research as well as our own contemporary data, we recommend moving toward a leadership model in schools that distributes key leadership functions between three primary roles:

- Operations leader

- Instructional leader

- Community leader

In this distributed leadership model, the notion of a “head principal” and assistants would not exist. These three roles would share equal authority in the building—albeit in different domains— and work together to lead the school. Actual titles, reporting structures, and job descriptions could be determined at the local level based on local context and organizational culture.

Operational leader. This role would lead the operational systems and work of the school. They would have primary responsibility for things like communication, scheduling, HR functions, budgeting, safety and security, busing, reporting, and sustainability of the building. As an example of the value this kind of role may have for a district, in the 5,000 student district of Acton-Boxborough in Massachusetts, investing in an ‘energy manager’, something the operations leader could do, netted the district $500,000 in annual savings in energy costs (Lieberman, 2023).

Instructional leader. This role would lead the academic systems and work of the school. They would have the primary responsibility for curriculum, instruction, assessment. The instructional leader would work with teachers to determine and execute the academic continuous improvement agenda in the building. Things that likely would fall in this leader’s portfolio would be MTSS, curricular selection, instructional coaching, data analysis, and professional learning related to academics.

Community leader. This role would lead the work that supports a humanizing culture of belonging in the school community. They would have primary responsibility for student and staff wellbeing, engagement of student voice and activism, social and emotional learning (SEL), school climate, and family and community engagement. As the leader who interfaces with organizations and the broader community in which the school is situated, they would champion the desires of the community, bring the ancestral knowledge of community members not only into the school, but also into the curriculum, and could lead resource mapping efforts to better integrate school and community. Ideally, this individual would see themselves—and be seen—as a member of the surrounding school community.

How the four T’s are addressed in this recommendation

Time. By distributing the primary leadership responsibilities in this way, each of the three leaders would have more time to focus on the incredibly important work they are leading. For example, if there is a shortage in staffing, or an eruption of behavior on the playground, the Operations and Community Leaders would be able to tend to these and the Instructional Leader would not be pulled away from a PLC or a classroom observation. Additionally the feeling of obligation to be in the building—a key barrier to to principals’ accessing professional development—could be lessened when there is a team of leaders with equal authority.

Training. With more specialized leadership roles, leaders can pursue more specialized training. It is not that the Instructional Leader is not concerned with the building climate or the SEL curriculum, but they can trust that as a team, the three leaders will have more depth of knowledge in their area, and can leverage their collective knowledge to effectively and collectively lead the building. Additionally, each position could have a clear succession plan with existing school staff members ready to step in at a moment’s notice to fulfill essential responsibilities.

Trust. Staff in the building would have a team of individuals to turn to, so the notion that only one person can make a decision or respond to a crisis could, in turn, foster greater collective efficacy among the staff. If, as suggested, the Community Leader is a member of the community in which the school is situated, this could lead to greater trust in the school among community members and parents.This model certainly requires trust among the three leaders; however,once trust is established, leaders’ feelings of isolation—which so many principals told us they felt as the lone administrator in the building—will diminish.

Transformation. This different model could lead not only to a transformation in the way a building leader does their work, it could also lead to more stability for the school community. Twenty-five percent of principals in our survey told us they plan to stay in their current role two years or less. With a change in leadership can come changes in the direction of the work in a building. With three leaders collectively focused on the same goals, a change in leadership in one role will not disrupt the course of the current efforts. Currently all principals and assistant principals in Minnesota must hold a principal’s license. While we would not argue that licensure is not useful, we might argue that it may not be needed for all leadership roles. For example, the Community Leader may bring critical experience from the community that no licensed administrator may have. We understand and believe that having a licensed principal in the school is needed, that by state statute (Minn. Stat. §121A.10), only a licensed school administrator can suspend a student, but much like those in student support professional roles (e.g., licensed guidance counselors, school social workers, school psychologists) often work collectively to support students and the school, this different leadership model could do the same. Finally, this model could genuinely lead to a disruption of white supremacy culture that is inherently built into the current model where there is one individual in charge. A more collectivist model could arguably be more culturally responsive as it stands to be more inclusive of diverse perspectives. For example, the Community Leader role would have the time and expertise to authentically engage parents and community in ways principals report they just do not have the time to do currently.

Minnesota Principals Survey (MnPS) policy and practice brief: executive summary

Introduction

The Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement (CAREI) at the University of Minnesota conducted the first biennial Minnesota Principals Survey (MnPS) in November and December 2021 to “elevate principal voice” in Minnesota education policy and better understand the working conditions, concerns, and needs of Minnesota school leaders. Overall, nearly 800 principals, assistant principals, and charter school directors working in public schools across the state responded to the survey, the results of which can be accessed at CAREI's Minnesota Principals Survey page.

To better understand school leaders’ experiences and solicit their ideas, we conducted a series of focus groups with 49 Minnesota principals in November 2022. The purpose of the Policy and Practice Briefs series is to summarize our findings and recommendations from the survey and follow-up focus groups in five focus areas: professional development, instructional leadership, culturally responsive school leadership, community engaged leadership, and staff and student mental health. This executive summary highlights key findings and selected recommendations in each of these areas, as well as overarching recommendations across the series, which can be accessed in full at here.

Professional development

As indicated on the 2021 MnPS, the type of PD participated in most frequently by principals—presentations at scheduled school or district meetings (70% of respondents)—was rated least useful. Oppositely, two of the types of PD school leaders participated in least frequently—the Minnesota Principals Academy (MPA) (7% of respondents) and doctoral coursework (5% of respondents)—were rated among the most useful. We asked focus group participants why they thought some forms of PD were more useful than others, and what might help them to better access high-quality PD.

Key focus group findings

- Participants shared that PD experiences such as MPA, doctoral coursework, and other forms of networking were especially useful because they involved sustained learning with peers, and often included access to relevant research findings that addressed their specific challenges.

- In order to leave school to attend PD, principals emphasized the need for a reliable backup plan so others could fulfill principals’ essential responsibilities as well as personal comfort with delegating.

Selected recommendations

- For policymakers. Ensure the 125 clock hours for principal relicensure are meaningful, and address content areas in which principals indicate low self-efficacy (e.g., Culturally Responsive School Leadership, Instructional Leadership).

- For system leaders. Invest in developmental approaches to principal learning that are ongoing and collective in nature (e.g., PLCs, collaboratively engaging in problems of practice) versus traditional “sit and get” PD. •

- For building leaders. Be proactive in developing a delegation structure that allows you to be out of the building and secure your supervisor’s buy-in.

- For principal preparation and PD providers. Ensure that professional learning programs leverage high-impact strategies such as one-on-one support, learning communities, and job-embedded learning.

Instructional leadership

A majority of Minnesota school leaders (62%) told us on the 2021 MnPS that they spend less time than they would like on instructional tasks (like curriculum, instruction, assessment, and PLC meetings), and a similar proportion (60%) reported spending more time than they would like on internal administrative tasks (like personnel issues, scheduling, and reports. Furthermore, seventy-nine percent (79%) of respondents also told us that they felt their primary role was to be an instructional leader, and yet only sixty-one percent (61%) shared that their supervisors ensured they had time to fulfill that role (Pekel et al., 2022). We asked focus group participants why time for instructional leadership was so hard to come by, and what might help.

Key Focus Group Findings

- Focus group participants told us that they often prioritized administrative tasks over instructional tasks to ensure student safety and effective operations, especially in light of persistent staffing shortages in their buildings.

- Principals shared they would have more time for instructional leadership if some managerial tasks were removed from their to-do lists, if they could share leadership with others in the school community, and if they could adequately staff their schools.

- Other participants felt that having more district-level support for instructional leadership—in the way of coaching, feedback, and opportunities for principals to provide input into district decisions—would help them manage this aspect of their role more effectively.

Selected Recommendations

- For policymakers. Consider funding incentives for districts that offer year-long paid internships for those studying to be principals with a focus on instructional leadership to enhance schools’ instructional leadership capacity.

- For system leaders. Partner with principals to identify administrative tasks that principals regularly do that other staff members—whether at the school or district level— could take on.

- For building leaders. Prioritize those instructional leadership tasks shown to improve student learning— like teacher coaching and feedback conversations— and discourage those that don’t, such as unannounced classroom walkthroughs.

- For principal preparation and PD providers. Conduct ongoing crosswalk of Minnesota administrative competencies with preparation coursework and experiences to ensure alignment, and work directly with school districts to craft meaningful internship experiences for aspiring school leaders. Use MNPS results to inform course/PD refinement.

Culturally-responsive school leadership

2021 MnPS survey responses reflected relatively low self-efficacy among principals in the area of Culturally Responsive School Leadership (CRSL), specifically. Across 49 leadership activities, creating culturally responsive assessments, designing culturally responsive curriculum, and supporting culturally responsive pedagogy were among the five least confident activities (Pekel et al., 2022). We asked follow-up focus group participants why they thought school leaders lacked confidence in carrying out culturally responsive leadership practices, and what they thought might help.

Key focus group findings

- Overwhelmingly, participants expressed a need for additional training in CRSL to feel more confident enacting it, with some even suggesting that such training be required for relicensure. Others identified fear or discomfort as a significant barrier to CRSL, while some cited a lack of time.

- In addition to more learning and networking opportunities as a way to develop their culturally responsive practice, school leaders wanted to know that district leaders would “have their backs” when implementing CRSL, especially in the context of community resistance.

Selected recommendations

- For policymakers. Require CRSL education as part of licensure renewal for school leaders and onboarding for school board members.

- For system leaders. Be prepared to support all leaders, but especially leaders of color in predominantly White schools, when they face resistance to culturally responsive work from staff or families. Use your positionality to explicitly support the decisions and actions of your school leaders.

- For building leaders. Access and leverage tools to self-assess your own equity leadership and CRSL practice.

- For principal preparation and PD providers. Require CRSL training in administrator preparation programs to meet or exceed the cultural competency requirement for educator license renewal in Minnesota.

Community engaged leadership

Results from the 2021 MnPS revealed that school leaders lack preparation, experience, and self-efficacy in several domains pertinent to community engaged leadership. For example, when we asked school leaders what content was missing from their administrative licensure coursework that they wished had been addressed, over a third selected family and community engagement best practices. Once on the job, 51% of leaders reported spending somewhat less or much less time than they would like on family and community interactions. We asked follow-up focus group participants to describe the barriers to community engaged leadership (CEL), and what would help them be more successful enacting it.

Key focus group findings

- Participants cited lack of belonging as a barrier to many marginalized families’ engagement in school. Furthermore, principals reported having limited time and resources to devote to community-engaged work, a general lack of know-how in this area of school leadership, and fractured, siloed, or fleeting approaches to CEL.

- School leaders desired dedicated staff to support CEL, in the form of parent liaisons, full time community engagement personnel, or more racially/ethnically diverse teachers.

- Participants recognized that effective CEL required them to engage in difficult and uncomfortable conversations with community members who have been historically marginalized by the education system.

Selected recommendations

- For policymakers. Provide community leadership pathways that do not require traditional licensing to ensure community voice is included in school and district leadership.

- For system leaders. Prioritize community engagement as a core component of the district’s work such that it becomes part of the cultural fabric of every school.

- For building leaders. Develop and institutionalize student, family, and community-focused listening/learning sessions with a plan to respond to input.

- For principal preparation and PD providers. Ensure course activities include practice in community engagement. Examples might include participatory action research, community-based equity audits, or report card deliveries/home visits.

Student and staff mental health

Of 49 leadership activities included on the 2021 MnPS, addressing staff mental health challenges was most frequently identified as posing the greatest challenge to school leaders. Furthermore, when prompted to identify the most significant ongoing challenges faced by their schools related to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2021 MnPS respondents identified staff mental health (68%) and student mental health (66%) far more than any other option, including loss of instruction, low student engagement, and active pushback from families related to COVID-19 (Pekel et al., 2022). In light of the significant challenges faced by building leaders related to mental health, we asked focus group participants to describe what kinds of mental health challenges they witnessed in their schools, their beliefs about the causes of mental health challenges, and what might improve the mental health of school community members.

Key focus group findings

- Among students, mental health challenges manifested most often as emotional dysregulation, absences, and bullying.

- School leaders felt that social media, societal upheaval, and other external stressors (e.g., loss of family income) were primary causes of student mental health challenges.

- Overall, 52% of participants across seven focus group sessions felt that having more personnel was the single best way to address the student mental health crisis. Other than personnel, more training in concrete practices to respond to emotionally dysregulated students and resources to support families directly were cited as promising strategies to address students’ overwhelming mental health needs.

- Among staff members, mental health challenges manifested as compassion fatigue, heightened emotions (e.g., outbursts), and retreating from work responsibilities.

- Focus group participants acknowledged that staff mental health challenges had improved since the 2021-22 school year, but were still significant.

- Participants viewed student behaviors, particularly those resulting from trauma, as primary causes of staff burnout. They also viewed staff members’ loss of a sense of purpose in their work and lack of voice in decision making as key factors.

- Ensuring time for staff planning and providing adequate staff coverage were top-cited strategies named by participating principals for addressing mental health crises among school staff members.

Selected recommendations

Recommendations relevant to the area of student mental health include:

- For policymakers. Invest in significantly improving the ratios of school psychologists, school social workers, and counselors in K-12, including through telehealth partnerships and workforce programs that incentivize careers in mental health.

- For system leaders. Encourage building leaders to adopt an equity-oriented universal mental health screener and establish a schoolwide system for social and emotional learning.

- For building leaders. Leverage needs assessments, resource mapping, and equity-oriented universal screeners to better understand schoolwide mental health needs, available resources, and gaps.

- For principal preparation and PD providers. Provide training on conducting a needs assessment and resource mapping to identify strengths, gaps, and priorities to improve the quality of mental health services.

Recommendations relevant to the area of staff mental health include:

- For policymakers. Enact legislation to foster healthy school climates, such as requiring annual school climate surveys, promoting an inclusive environment through antidiscrimination policies, and requiring adoption of alternatives to exclusionary discipline that keep youth in school.

- For system leaders. In the short term, identify systematic ways to address acute staffing shortages by recruiting and retaining substitute teachers. In the long term, collect data from school staff about their working conditions, and use it to inform strategies to prevent burnout, staff absences, and turnover.

- For building leaders. Work towards reducing staff burnout by addressing the issues of staff planning time and staff coverage. Consider innovative approaches to scheduling.

- For principal preparation and PD providers. Help aspiring principals develop the skills, mindsets, and behaviors that have been consistently shown to promote positive school working conditions and reduce staff burnout, such as fostering trust, protecting team planning and learning time, and including staff members in decision-making.

Overarching themes and recommendations

As we heard from Minnesota principals via the MnPS and followup focus groups, four recurrent themes emerged as leaders’ top needs, which we have termed, the “Four T’s.” These include:

- Time to carry out their most impactful leadership functions

- Better training, especially in instructional leadership and culturally responsive leadership practices,

- The trust and support of their supervisors in carrying out their work, and

- Transformation of principals’ job descriptions and how principals experience professional development.

While distilling findings from a complex, comprehensive survey and related focus groups is challenging, we offer the following as two overarching recommendations for this Policy & Practice series: a developmental approach to initial training, internship, and ongoing professional development; and a new school leadership model.

Recommendation 1: A developmental approach to initial training, internship, and ongoing professional development

As we considered the progression of principals’ experiences— from their teaching careers, through their initial licensure programs, their administrative internship, and into the principalship—we recognized in the voices of participants an overarching lack of continuity and cohesion in their professional development. Recommendation 1 proposes that those who train, mentor, coach, and supervise principals consider, more holistically, the professional goals and needs of each principal, much as we ask teachers to consider the whole child in determining developmentally appropriate and culturally responsive methods of instruction. Embedded within this recommendation are specific suggestions for ensuring each leader has sufficient preparation and practice to enact culturally responsive, instructional leadership across content areas and contexts, as well as concrete ideas for ensuring that the time aspiring and practicing principals spend on their professional learning is purposeful and impactful.

Recommendation 2: A new school leadership model over half of leaders tell us their workloads are not sustainable.

They tell us they lack the time and confidence to be effective instructional leaders, and struggle to engage and include family and community members, particularly those with marginalized identities, despite the painful awareness that such leadership functions are critical to their schools’ success. Instead, they “put out fires,” responding to crises, fulfilling high-stakes reporting requirements, and supervising the lunchroom. How the principalship is currently designed does not engender the kind of school leadership most likely to promote positive school climates and improved student learning (cite, cite). Rather than continue to uphold a school leadership paradigm characterized by work overload, burnout, and a precarious reliance on a single person, we propose a new model of school leadership that distributes essential leadership functions across multiple staff persons and teams. Specifically, we recommend moving toward a leadership model in schools that distributes key leadership functions between an operations leader, an instructional leader, and a community leader, recognizing that specific titles and job descriptions could be determined at the local level. In this distributed leadership model, the notion of a “head principal” and assistants would not exist. These three roles would share equal authority in the building—albeit in different domains—and work together to lead the school.

Conclusion

It is our hope that by elevating the experiences of practicing Minnesota school leaders, we can contribute to improving their leadership self-efficacy and impact on students and teachers in all corners of the state. The four T’s of Time, Training, Trust, and Transformation offer those who support principals’ work— whether at the legislature, at institutions of higher education, or at the district office—a useful framework to guide decision making and resource allocation that honors the substantial challenges and complexities facing school leaders today.

Minnesota Principals Survey (MnPS) policy & practice brief: community engaged leadership

About

The purpose of this policy and practice brief is to summarize our findings and recommendations from the MnPS and follow-up focus groups in one area in particular: community engaged leadership (CEL).

First, we offer some background information on CEL. Second, we review survey data and corresponding themes from focus groups pertaining to CEL. Third, we highlight existing research on CEL to further explain these findings and understand their implications. And finally, we close with a series of recommendations for practitioners and policymakers.

Introduction to community engaged leadership

As detailed in the full report of findings from the 2021 MnPS, fewer than half of Minnesota school leaders (48%) report living in the community in which they work, with only 32% of Twin Cities leaders indicating as such (Pekel et al., 2022). The distance between the most disenfranchised and under-resourced school-communities and their school leaders presents significant barriers to understanding needs, recognizing assets, building relationships, and leveraging administrative privilege to advocate and develop partnerships. These critical leadership behaviors contribute to community engaged leadership, which is broadly defined by DeMatthews (2018) as:

…how principals take on a broad range of social justice issues within their schools and communities and how they work with others to prioritize their foci… When [community engaged leadership] [is] reflected in the principal’s values and leadership actions, principals can catalyze and meaningfully engage teachers, students, families and communities in transformational change (pp.139-140)

- School leaders who are truly engaged in their communities have the potential to: Shift school cultures, ensure that families and local community members are served and connected to additional forms of capital, decrease disciplinary infractions, increase graduation rates, increase academic achievement, and increase attendance (Green, 2015). However, school leaders are rarely trained to center community in school-based decision-making (Stanley & Gilzene, 2022). Hence, school leaders often lack the knowledge and capacity to lead school-communities jointly.

In the U.S., research on community engagement is clear that strong connections between community, families, and schools is vital for school improvement (Stanley & Gilzene, 2022). Yet scholars continue to highlight the disconnect that exists between schools and marginalized members of their communities, who have historically—and repeatedly—been excluded from school spaces.

Community engagement presents itself in several forms. In a review of the literature, Darrius Stanley (2022) describes how research has framed community engagement as: culturally responsive school leadership, culturally responsive family engagement, leveraging youth voice and activism, community-based research for improvement, leveraging community-based forms of capital for improvement, and community-school shared governance/decision-making. Each of these offer ways to engage with historically disenfranchised groups, but as Stanley (2022) argues, schools tend to lack the know-how or training to engage in this type of work. Despite the numerous ways for community engagement to occur, at the crux of community engagement, argues Muhammed Khalifa, it is more than simply showing up in the communities you serve, but also “an engagement in and advocacy for community-based causes” (Khalifa, 2018, p.170).

Perspectives on community engaged leadership

This section presents themes that emerged from two focus groups (one of Twin Cities leaders, and one of Greater MN leaders) specifically dedicated to the topic of community engaged leadership. Focus group questions were developed in response to MnPS survey findings to better understand how leaders define and enact CEL, the barriers they face in doing so, and what supports they need to improve their community engagement practice. We begin with a brief description of survey findings pertaining to CEL, followed by summaries of responses to each focus group question.

Survey says: community engaged leadership is lacking

Results from the 2021 MnPS revealed that school leaders lack preparation, experience, and self-efficacy in several domains pertinent to community engaged leadership. For example, we asked school leaders that completed an administrative licensure program what content, if any, was missing from their administrative licensure coursework that they wished had been addressed. One of the top three areas selected by respondents was family and community engagement best practices, selected by 36% of respondents. This is further illustrated by their lack of comfort in communicating about race, gender, and culture with families and community members, a top three “greatest challenge” among 16 culture and climate activities, preceded only by addressing mental health challenges of staff and students (Pekel et al., 2022).

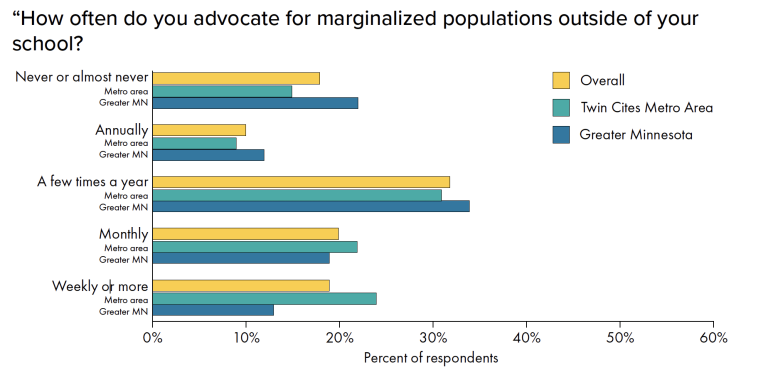

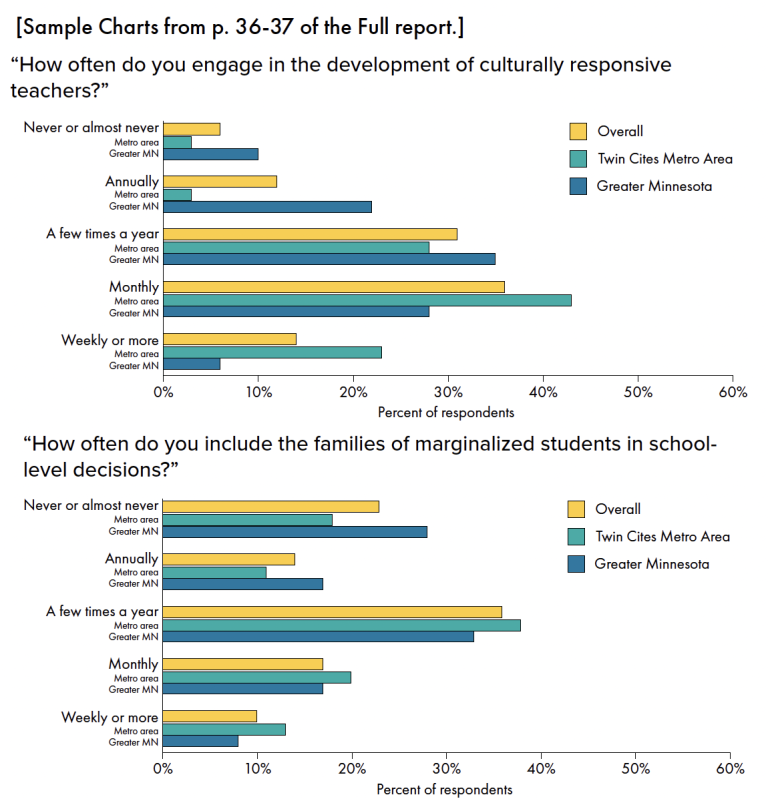

Once on the job, 51% of leaders reported spending somewhat less or much less time than they would like on family and community interactions. Additionally, 42% of respondents selected engaging families in school-level decisions as their “greatest challenge” among 15 management and decision making activities. Indeed, only about 1 in 4 leaders reported including the families of marginalized students in school-level decisions on a monthly or weekly basis (27%), and nearly the same proportion (23%) reported never or almost never doing so (Pekel et al., 2022).

Other data from the survey suggest that leaders are making attempts to be engaged in community events outside of school, with nearly 80% of respondents saying they do so at least a few times a year, if not more frequently (Pekel et al., 2022). However, community engaged leadership goes beyond just attending events, and can and should include advocating for the communities served and their causes (Khalifa, 2018). Only 39% of respondents reported engaging in advocacy for marginalized populations outside of school on a monthly or more frequent basis (Pekel et al., 2022).

How do principals define community engaged leadership?

In our focus groups, we learned that education leaders have various definitions of community engaged leadership (CEL). Many participants described it as a “two-way street,” referring to the bi-directionality of community being in school spaces as well as school finding its way into community spaces. The ability to build trust to create this bi-directionality was a prominent factor participants highlighted as crucial to engaging in CEL work. This work to build trust requires time and intentional effort on the part of school leaders, as well as a relinquishing of a top-down approach to creating a school vision. Instead, leaders aspired to build a vision together with the community. Sometimes, according to participants, CEL can look like listening sessions, but ultimately leaders reflected that it looks different depending on where you stand.

I think oftentimes we as leaders kind of have that hierarchical structure where we try to set the tone for everything that’s going on. But unless you’re out in the community to really engage and find out what the needs are, and allow them space within our community to come in and have some type of quality and focused ability to share their thoughts and their ideas, that will help us.

I would define it as two parts, just like everyone else. It’s how do we get families and community members engaged in leadership in the building, and how do we get leadership engaged in the community.

What are the barriers to community engagement?

In response to survey findings indicating that Minnesota school leaders faced substantial challenges in the area of family and community engagement, we asked focus group members to help us understand the particular barriers they faced to engaging in CEL practices. Themes in response to this question included: community members’ lacking a sense of belonging, limited time and resources, lack of know-how, and leadership turnover that threatens the continuity of engagement efforts.

Lack of belonging. Some participants identified a missing sense of belonging as a barrier to creating inclusive environments for and reaching the marginalized families served by their schools. Lack of a sense of belonging directly impacts parents’ and students’ comfort navigating school spaces, both during and after the school day. In some cases, lack of belonging was institutionalized by building policies that restricted some parents from entering the premises due to the lack of government-issued identification.1

Because of the absence of belonging on the part of community members and parents, educational leaders reported having trouble reaching the marginalized community members they wanted to hear from through community engagement events. Further exacerbating this problem was a lack of diverse staff, as well as disproportionate attendance at such events by more affluent and predominantly White families.

1. In March 2023, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz signed a bill into law that would allow undocumented immigrants to obtain a Minnesota driver’s license, which may reduce this school access barrier for many families.

They don’t see it [school] as a place for them, and sometimes not for their kids either. So I think that’s a barrier.

We’re trying to get more stuff happening, not just outside of the [school] day, but even in the [school] day to engage with our students, and sometimes our security measures do get in the way of people if they don’t have this [document], or don’t have the security clearance, or even people from other countries might not have the right documentation, or background checks to be able to come in and speak to classes about their life experiences. So that is a barrier sometimes as well.

Limited time and resources. Many participants reported not having adequate time and resources for undertaking community engaged work. They felt that neither the Minnesota legislature nor their districts had dedicated enough funding to allow the schools to properly enact CEL. Similarly, some school leaders felt that effective CEL required a full time staff member dedicated to overseeing community engagement. In more than one instance, school leaders acknowledged that community engagement was a low priority in the context of limited staffing.

It has to be really planned out, really well thought out. We just can’t make it a pivot very quickly, because we have to get language lines. We have to get interpreters. We have to get all of the necessary things in place in order for us to be successful....But to engage the community is very difficult then, because of the time and energy that it takes.

We’re just underfunded, and so I don’t have enough staff and [can’t] hang on to the staff I have, because we don’t pay well enough to compete… The workload of a school administrator or principal is that there’s a lot on the plate. Especially when you get to out-state [Greater MN] and you don’t have specialists in every area. So all of that gets dumped on the leader of the district or the school building in particular, and sometimes the community engagement will take a back seat to the things that have to get done in the meantime, or your school is not completely running.

Lack of know-how. School leaders stated that they have a desire to foster a high level of community engagement but are not equipped with the knowledge or tools. This creates a hesitancy or fear on the part of leaders, teachers, and other staff in the school to reach out to marginalized communities, in turn further distancing school and community. In connection with the barrier of belonging, some expressed doubt in their own and their staffs’ ability to understand, learn about, and connect with what families are experiencing in ways that can create genuine, appropriate opportunities for community engagement.

I think another barrier is just the how. What can I do?...I can’t say that I have a really deep well of tools to help bring the community in… and I know I’m a ways out of my teacher and administrative program, but I don’t feel like I was well prepared with a tool or a toolkit of ways to engage the community.

Some of our educators are afraid to reach out to our families… Some of our staff don’t have this skill set, or don’t know the ‘how’ to reach out to certain families, which just creates a chasm that just keeps growing and growing.

Lack of continuity. A recurring theme discussed in CEL focus groups was the nature of community engagement within the broader school system. Some leaders felt that CEL, as practiced in their districts, was very fractured, or not seen as a core part of the school’s work. Other leaders were frustrated with changes in district leadership that impacted the fidelity of community engaged work. As leadership changes, so too do school systems’ approaches to and priorities surrounding community engagement.

I’d say one barrier in my experience is continual change of leadership. I think the Superintendent’s tenure…is like 2.8 years in one job [on average]. So lack of stability with a vision.

What does successful community engagement look like?

We asked focus group participants to share with us what they saw as successful community engagement. Some shared concrete examples of what they viewed as community engagement efforts, while others shared the kinds of evidence they look for to gauge whether community engagement efforts had been successful. In the former category, one example provided was connecting families to expertise and information. School leaders recognized that some families leaned on schools for information dissemination, particularly around how to support their student(s) from home during the pandemic. A second example was the development of sustainable career pathways for students. For instance, some schools connect students with local employers that provide training that can lead to employment opportunities within the community.

In the latter category—evidence leaders look for to gauge the success of CEL work—several examples were provided. One leader felt that successful CEL looked like parents being able to support their students’ learning at home and communicating the importance of learning to their child, buttressed by having a positive outlook on their child’s school. Another example of evidence of success in the area of CEL was students and their families feeling safe enough and welcome enough in the school building that they wanted to be there and regularly showed up.

Successful community engagement looks like students wanting to come to school.

Covid particularly made us realize how much the community relies on us to be the expert of all things, or to connect them with resources.

What would help to improve community engagement?

We asked focus group participants, “What resources, supports and/or learning would facilitate improvement in the area of community engagement?” Many leaders communicated a desire for more dedicated staff to do community engagement work. Others acknowledged that principals needed to courageously “dig in” to community engagement work, despite it often being uncomfortable. In light of focus group participants highlighting a lack of know-how to do community engaged work, as presented previously, we were surprised that no participants identified training as a need.

Dedicated staff. Previously identified as a barrier to community engagement, dedicated staffing to support community engagement work was a recurring need shared by participants. Whether in the form of parent liaisons, full time community engagement personnel, or more diverse teachers, leaders felt they needed additional staff capacity to begin or expand community engagement work.

When it comes to resources, I used to have a parent liaison. I had to cut that position years ago due to funding, so I don’t have anybody specifically dedicated to that work.

Learning in discomfort. Focus group participants also shared the need for school leaders to engage in difficult and uncomfortable conversations to move this work forward. Some who had had success with community engagement had found ways to have such conversations, where difficult subjects could be raised and discussed in a respectful manner and across lines of difference. In fact, the theme of discomfort being a necessary component of community-engaged work arose in response to several focus group questions.

I think that the more principals can get really comfortable with digging in and feeling discomfort, and push forward, then that empowers us and equips us to be able to train our faculty to do the same.

More training? Surprisingly, despite reporting that they lacked “know-how” in CEL, leaders did not talk extensively about wanting more training. One participant felt that having a “toolkit” for CEL would be helpful. Another highlighted culturally-specific community partners as “critical” for their schools’ learning and growth in the CEL domain. Many others had appreciated the different learning opportunities they had had pertaining to CEL, ranging from university coursework to training offered by non-profit organizations to district professional development. However, they did not report needing additional training. Rather, responses emphasized the capacity and courage dimensions of community engagement, as noted above.

You know, I think the educational component is important, for school leaders to know and understand this work… But, for me, and this might be too simplistic of an answer: it’s money. If we all had a full time person focused on community engagement, we’d see massive increases. I think. If it’s just another layer that principals are supposed to do on their own, it gets difficult, and not, I don’t think, due to lack of engagement on the principal’s part. It’s just, it’s one more thing. So, I think, [having an] individual whose job it is to do this [is needed] because it’s critically important work. I don’t think it should be just another thing. It’s got to be somebody’s charge, I think.

What the research says: community engaged leadership

Theoretical and empirical research on CEL offers numerous insights in response to our survey and follow-up focus group data. The sections below highlight recent research spanning multiple dimensions of leadership practice, including:

- How leaders understand the directionality of community engagement

- Key practices that are foundational to CEL

- The role of community advocacy in building trusting relationships and fostering inclusion

- How leaders position school spaces as community spaces

- Capacity for CEL through a human capital/assets-based lens

- Partnership with community organizations

- Alignment of school/district leadership and community priorities, and

- Addressing the discomfort dimension of community engagement.

Reimagining community engagement

MnPS respondents and focus group participants shared that they felt underprepared to participate in CEL, and had limited understandings of what community engagement entailed. Scholarship on CEL highlights how principal preparation programs often miss the mark in developing school leaders’ ability to cultivate school-community relationships. Oftentimes, school leadership preparation positions community engagement narrowly, as appreciation of diversity or multiculturalism. Scholarship on CEL critiques the lack of “authentic, asset-based community engagement for social justice” among educational leaders (Stanley & Gilzene, 2022, p.1), as well as the unidirectional focus on how schools contribute to the community, instead of also considering—in a non-extractive way—what assets the community can provide to the school. Leadership programs tend to omit in-depth historical contextualization of community spaces, or fail to center community/youth leadership, leaving school leaders “ill-prepared to lead their communities” (p.3).

Listening, Engaging, Advocating and Partnering (L.E.A.P.)

Stanley and Gilzene (2022) offer a framework in response to leadership preparation shortcomings. Listening, Engaging, Advocating, and Partnering (L.E.A.P.) is a research-informed framework designed and conceptualized to challenge the field of educational leadership, including educational leadership practitioners, to envision their roles as school-community leaders. This framework centers four distinct, research-informed pillars: 1) listening, the ongoing practice of centering students, families and community members in school-community decision-making; 2) engaging, developing and sustaining, deep, reciprocal relationships with students, families and community members; 3) advocating, leveraging the administrative platform to advocate for and with communities to accumulate resources; and 4) partnering, building sustainable and reciprocal partnerships which “horizontalizes” school-community leadership, shares decision-making with communities, and focuses on ongoing joint school-community improvement and development.

The L.E.A.P. framework draws directly from other key conceptual leadership frames including Culturally Responsive School Leadership, Youth-Engaged Leadership, and Culturally Responsive Family Engagement, to name a few. This scholarship serves as an initial framing of community-engaged educational leadership and a call to leadership preparation programs, as well as practicing administrators, to frame their work as community work. That is, educational leadership programs must prepare school and district administrators to engage communities in the everyday practices, procedures, accountability structures, policy-making processes, curricular decisions and other important aspects of the school and district. More importantly, school and district leaders must be trained to see historically disenfranchised communities as assets in the framing of educational equity, academic success, and vision(s) for the futures of youth and communities.

Building trust and belonging through community advocacy

MnPS focus group participants told us that one major barrier to community engagement was a pervasive lack of sense of belonging throughout the minoritized communities they serve. However, principals are well-positioned to redress this challenge through improving relationships with the community. Research tells us that principals play a large role in establishing and nurturing relationships between schools and the communities they serve. Khalifa (2012) suggests that leaders that spent time focusing on community-relevant noneducational issues were more successful in community engaged work because they were able to bridge the gap between community and school, building the trust and rapport required to foster inclusion. Dr. Terrance Green (2015) asserts that principals are positioned to support local reforms that impact communities by establishing strong ties with community centers and other local organizations.

This civic capacity (Hausman & Goldring, 2001) becomes even more important given that many school leaders live outside of the communities they serve, as indicated by 2021 MnPS findings. Placing the community’s causes at the forefront of the school leadership agenda will help leaders gain access to the trust and credibility they often seek (Khalifa, 2018, pp. 170-171). It is important for school leaders—many who identify as White—to acknowledge that community engagement looks different in minoritized communities than in White communities due to the historical and current practices of exclusion of Black, Brown, Indigenous and other minoritized communities (p. 172). Such exclusion has long fostered distrust in institutions such as schools, and school leaders must demonstrate genuine and ongoing commitment to minoritized community causes to regain that trust.

Positioning schools as inclusive community spaces

Though schools have historically not been a safe or inviting space for marginalized communities, when community engagement does take place inside the school building, it is important to consider how to make school spaces more inclusive and community focused. School leaders can accomplish this by positioning schools as a spatial asset: using extra space in the school to develop a community-based health clinic; providing exercise and wellness facilities at low cost to the community; bringing in local experts to provide free/low cost training and support to families; utilizing school space to provide GED and financial literacy courses for families (in partnership with local educators/experts); using extra school space to develop a community garden—and leverage it to teach culinary arts, agriculture and provide fresh produce to divested communities (Green, 2015).

Below are further examples of how to foster new relationships in places that have historically marginalized or excluded minoritized communities:

- Developing partnerships with local institutions like universities to shift the organizational culture to be more inclusive;

- Fostering a college-going culture by bringing in college students as tutors and mentors;

- Partnering with neighborhood organizations to start a community garden;

- Connecting with local city-based programs that focus on student leadership and development (Green, 2015).

Through the inclusive practices above, marginalized community members can find their way into schools on their terms, choosing to participate in community engaged leadership activities that are prioritized as central to schools’ operations, as opposed to being viewed as “extracurricular.”

Framing CEL as everyone’s work

We heard focus group participants lament the limited time they had to engage in CEL. Research offers an alternative way to frame community engagement work that relies less on the capacity of the individual building leader. Stanley and Gilzene (2022) suggest that schools leverage the human capital already built into their school communities, including relationships with families. Families are untapped experts on student heritage and cultural traditions who can be enlisted to help bolster and support a school’s curriculum. Parents and community leaders can serve on school equity teams, supporting hiring decisions, budgeting, and even policy changes.

As schools struggle to hire staff with the necessary experience(s) or expertise, schools can leverage those of the community members they serve. This type of community leverage is already taking place in some districts. Grow Your Own programs2 are one example. Traditional teacher licensure programs have historically excluded marginalized parents and community members interested in contributing to their children’s education. However, Grow Your Own programs have been helpful in creating alternative, sustainable pathways for community members to work in schools (Gist et al., 2019). These programs not only help to address staff shortages, but, more importantly, they offer a way to structurally integrate marginalized community members and their feedback into schools.

2. “Grow Your Own” programs are designed to offer alternative teacher licensure pathways to individuals underrepresented in school systems (namely, people who identify as Black, Indigenous, or as people of color), typically targeting those who work in schools already as paraprofessionals or educational assistants.

Partnering with community organizations

Another way to bring community into schools is by partnering with local organizations to bridge gaps in access to services and to fund new initiatives. Partnerships with healthcare providers, local businesses, and community foundations can infuse critical resources into school-communities. As mentioned by one focus group respondent, local fraternities and sororities may also be an untapped resource for schools (Stanley & Gilzene, 2022).

Aligning leadership to community priorities

Respondents shared that inconsistent district leadership posed challenges for CEL, and how difficult it is to engage in CEL when it is not the focus of an incoming superintendent. One approach offered by Green and Rogers (2019) is to leverage a Community Equity Literacy Leadership Assessment (CELLA) to inform school and district improvement in the area of CEL, shifting the traditional top-down conception of school leadership to a more collaborative and community-oriented model. While the CELLA tool has been tested and refined among school leaders as a means of evaluating their skills and knowledge in this area, similar tools could be developed and leveraged among district leaders and even school boards to inform superintendent selection. Rather than selecting a superintendent based solely on what they can bring to the district, for instance, school boards leveraging a community collaborative assessment might instead select a candidate that demonstrates alignment with— and commitment to working towards—the desires and needs expressed by the school and community.

Leaning into discomfort

Lastly, MnPS focus group participants shared that effective CEL required experiencing some discomfort in the learning and improving process. Though more research is needed on how leaders navigate discomfort in CEL contexts, much can be learned from related work in the areas of culturally responsive practices. Our brief on Culturally Responsive School Leadership, also in this series, includes resources and research that may be helpful to school and district leaders that find discomfort to be a barrier to community engagement.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations for policymakers and practitioners in light of MnPS survey and follow-up focus group findings as well as the research presented above pertaining to effective community engaged leadership:

For policymakers

- Fund and evaluate the effectiveness of community schools that are inclusive of community feedback, and disseminate promising practices.

- Remove financial constraints to marginalized community members’ serving on school boards or in district leadership positions (e.g., by providing equitable salaries) so they may contribute to the vision and goals of the district.

- Provide community leadership pathways that do not require traditional licensing to ensure community voice is included in school and district leadership.

- When creating policy, consider opportunities to bring together community-serving organizations—with specific attention to including minoritized communities—and schools and districts to inform strategy and funding.

For system leaders